Two key heuristics guiding my research into politics and policy

Hayekian welfare states + public policy is the result of a competitive political process

Far too many people, when they read the news about Congress, see the action through a lens of power. This monocausal view of politics makes you miss some important details.

Of course, you need to focus on power, but also remember what Kenneth Burke said: A way of seeing is also a way of not seeing—a focus upon object A involves a neglect of object B.

Power is one frame for understanding, but it is one model among many. And to be clear, the term model does a lot of work. It is encompassing and includes a range of related ideas. Models, frames, frameworks, shorthands, or heuristics are all tools and organizational schemas that help to break down and simplify complex data.

Those of us working in public policy clearly traffic in models. Rather than being coy about it, we must embrace our models, interrogate them, and understand their limits.

Two heuristics that I cannot shake stem from the work of Friedrich Hayek and James Buchanan. The first concerns information, and the second concerns process. Both are important views to adopt when understanding the opaque world of politics and policy.

Hayekian welfare states

Friedrich Hayek's research aimed to understand how knowledge gets embedded into economic systems. His key insight, which netted him a Nobel, was that knowledge is naturally dispersed throughout society.

Reading Andreas Bergh (2019) last year brought this into focus for me. This paper asks two questions. First, if big government harms economic and social outcomes, why aren't the nations with the most intrusive governments doing worse? And following this, why don't more countries follow the strategy of Sweden and other Scandinavian states to provide for their citizens?

To answer those questions, Bergh introduces the concept of Hayekian welfare states and argues that it can help to answer both. A Hayekian welfare state refers to the “tendency to evolve through trial and error and the tendency to have a large public sector without being highly exposed to the Hayekian knowledge problem described by Hayek (1945).”

Politics and policy have long been dominated by a big versus small government divide. At the end of the day, this boils down to fiscal capacity. In this thinking, we will tend to ask, how much does the government take from your wallet?

A Hayekian understanding of government is orthogonal to the fiscal question and focuses our attention on knowledge within the system. It is a separate line of analysis from the fiscal one. Bergh makes it clearer with this table which puts the fiscal capacity question vertically and the Hayekian knowledge question vertically:

Few appreciate how little information sharing there exists in many government institutions, but Matthew Yglesias had a great example of it:

I remember showing this chart about Democrats’ paid leave proposal to a friend who works in political journalism. She was genuinely very surprised — she thought the proposal was for universal parental leave and had no idea that over 60 percent of the benefits were for personal sick leave or that 30 percent of new mothers wouldn’t qualify for coverage.

After that, I surveyed some members of Congress and chiefs of staff I know on the Hill, and about half of them didn’t know either. This was not secret information — it was in the CBO score — but the fact that Democrats had so little information about the content of their own policy was a sign, I think, of how impoverished the policy debate has become. Nobody was out there making the case that “hey, the part of this that people are fired-up about is the leave for new parents, let’s narrow the bill but make the coverage universal and it’ll be cheaper.” And because nobody was making that case, nobody was making the affirmative case for the structure they decided on.

Indeed, even the most well-informed are uncertain of outcomes. As Jason Furman explained in Maxims for Thinking Analytically, when he arrived in Washington, he was surprised to learn that,

The best political and legislative aides had only two possible probabilities for events occurring: zero and one. One of the top ones would say ‘I was in Congress for years, and I can tell you there is no chance they will pass this’ – weeks before it passed. Or ‘In all my decades in Washington attaching such and such to the bill has never failed to get it passed,’ just before months and months of failure to get it passed.

Bergh (2019) fits squarely within a literature first laid down by Herbert Simon. Indeed, as I have noted before, my view of information is indelibly shaped by Simon’s “Designing organizations for an information-rich world.” His logic is generative because it games out the impacts of an information-rich world. And it is driven by a simple yet powerful question: In a surfeit of information, what gets economized?

Simon’s reasoning is always worth quoting in full:

[I]n an information-rich world, the wealth of information means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes. What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.

In applying this logic to individuals, Simon was the first to name and describe the attention economy. And in applying this logic to organizations, Simon brought attention to the processes that condense information for groups and organizations. The key question for understanding information in systems is to understand what is being “withheld from the attention of other parts of the system.”

This is the driving question of our age. What is being “withheld from the attention of other parts of the system” is a throughline behind all of our contemporary scandals like Cambridge Analytica, Hunter Biden’s laptop, Section 230 debates, shadowbanning, content moderation, free speech online, censorship by Big Tech, and on and on.

But thinking about how information is being withheld is also a powerful lens to understand how policy and politics work in practice.

Policy is the result of a competitive process.

The other powerful heuristic I saw everywhere this past year comes from James Buchanan. His classic text on order complements Hayekianism well. "Order Defined in the Process of its Emergence" is a short piece but an incredibly important turn in logic. As he pointed out, the order of the market “emerges only from the process of voluntary exchange among the participating individuals."

Buchanan continued that “the allocation-distribution result, does not, and cannot, exist independently of the trading process. Absent this process, there is and can be no ‘order.'”

All of this clicked for me when I read Marta Podemska-Mikluch's paper on Polish pricing of reimbursed pharmaceuticals which reframes Buchanan for public policy:

By assuming that policy is an object of choice, economists have no alternative but to naively hope for a decision-maker sensitive to economic logic. An alternative approach is to think of policy, not as an object of choice but as an outcome of a competitive process.

I think that understanding is key to the movement in Congress. Policy is not an object of choice but is an outcome of a political trading process.

It is a bit of a banal observation to say that policy is an outcome of a competitive political process, but the shift in framing helps to clear up some confusion. As Podemska-Mikluch continues,

In some cases, it is a benevolent dictator, in others a special interest group, but most commonly a median voter is thought to be responsible for choosing a policy from options proposed by various individuals and groups within the society. No matter which kind of a decision maker is considered, the implication is the same: policy is an object of choice. Conceptualized in this manner, the process of policy formation is not much different from shopping at a supermarket where one picks and chooses the ingredients for the optimal policy (Wagner 2010). As a result, much of the story is missed, i.e. unintended consequences that are generated in interactions between individuals pursuing their plans and goals.

If policy were a choice made by the median voter, we’d have immigration reform, and yet, not even the EAGLE Act can get past Congress. Immigration is more popular than ever, even as its passage seems less likely. What’s stopping immigration reform are all the veto players in the process.

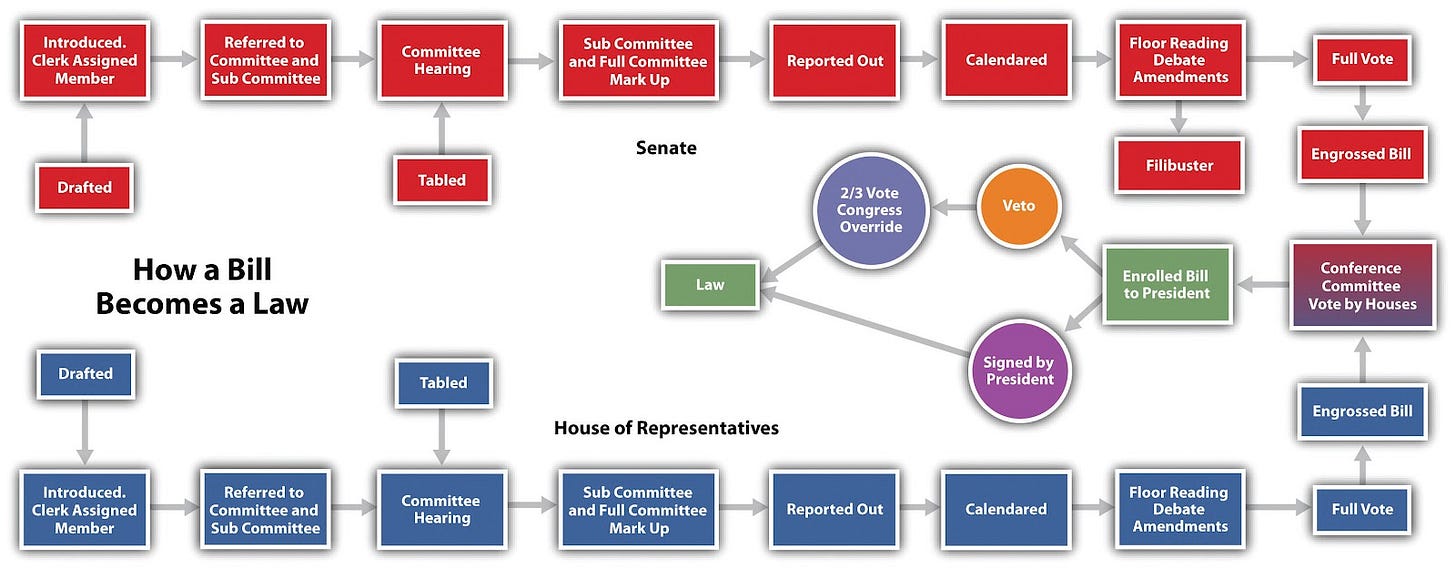

Legislation is the end product of the committee process, at least in Regular Order. Each time a bill can pass a checkpoint, it gains steam and becomes more likely. Passing out of committee and onto the House floor, for example, means that the bill has a better chance of becoming law. The more steps you complete on the board, the more likely the bill becomes.

So creating legislation isn’t as simple as deciding the correct choice. Instead, it is an emergent phenomenon produced from the competition of various actors, all jostling for status, constituent support, legal clarification, and prohibitions within a competitive institution. And then these bills have to get interpreted through the administrative state.

Seeing policy as the outcome of a competitive process explains the power of Senator Manchin. In the last session, he had a coveted position of power because he was the most conservative member in the Senate in a 50-50 split with the Republicans. But his dealings on his permitting bill show the limits of that veto power. As Politico reported,

Manchin’s permitting bill began as a coda to his outsized leverage in a Congress that found him playing decisive roles in everything from a bipartisan infrastructure law to post-Jan. 6 presidential certification reform to two massive Democratic-only bills. The centrist hatched a two-part deal with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer this summer: First Manchin would help pass a party-line climate, health care and tax bill, then Schumer would take up a plan to expedite big energy projects including West Virginia’s own Mountain Valley Pipeline.

But Manchin’s final major priority after a stretch in which everything broke his way needed the support of Republicans. And there were simply too many problems for him to solve in too short a time after releasing his legislation just last week. His home-state GOP colleague Sen. Shelley Moore Capito has her own permitting bill, and Republicans who want to defeat Manchin in 2024 largely have no desire to help him out of a jam.

“He thought he was going to pass a bill and get it signed into law. He miscalculated, is the nicest way I could put it,” said Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), a close ally of Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, who whipped against Manchin’s effort behind the scenes and publicly pushed for its defeat on Tuesday.

If we move away from a pure power lens and towards one considerate of knowledge problems and production problems, then Manchin’s problems in permitting reform make sense. Manchin was the final vote only in a negative sense. He didn’t have the clout to advance all of his bills, but he did have the ability to take provisions away. As Jim Newell explained in Slate, “He’s kind of being squeezed because he is not determining the agenda, but he is determining what may or may not cut through as part of that agenda.”

Determining what may or may not cut through is an underappreciated part of government operations. This is why I spent so much time working on vetocracy last year because in many political processes, “too many actors have veto rights over what gets built.”

Vetocracy is related but separate from the broader problem of red tape. Red tape, permitting, and other limitations regulate conduct. Laws that regulate conduct need to be judged by their own merits, but vetocracy isn’t regulation of conduct. Vetocracy is about the needless delays created through excessive veto points throughout our institutions. There are a lot of players involved in permitting and all it takes is one to slow everything down. Vetocracy is about the excessive accretion of voice that slows down normal processes.

In other words, public policy is not as much a problem to be solved as it is the result of a process. And that process can be slowed down by veto players. Going slow is costly.

In a recent research roundup, I highlighted Neupane and Adhikari's (2022) study on permitting costs. These two researchers modeled the costs of 11 geothermal projects in California, Nevada, and Utah and then calculated how the variation in review times can change the viability of a project. Longer CEQA/NEPA review timelines mean less time to earn returns, pushing the cost upwards. The effect was an electricity cost increase by 4% to 11% via the simplified levelized cost of electricity (sLCOE) method. These extended review timelines led to $64 million to $227 million in revenue losses. For some projects, these extended delays meant the death knell. Slow permitting could sink a geothermal project.

Just as permitting processes can affect the viability of a geothermal project, understanding the interplay between politics and policy often requires digging beneath the surface to uncover the underlying processes.

These two heuristics aren’t the only ways to understand government processes, nor are they revelatory, but they are underappreciated. Adopting multiple perspectives, including those centered on information and process, is the only way to gain a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the opaque world of politics and policy.

"Politics and policy have long been dominated by a big versus small government divide. At the end of the day, this boils down to fiscal capacity. In this thinking, we will tend to ask, how much does the government take from your wallet? "

The dichotomous choice between "big" and "small" government largely missed the point. The real question, to put it bluntly, is do we want a "smart" or "dumb" government. Our policy structures constrain or enable us, on a national/civilizational level, but also on an individual level.

Policy should be optimized so as to minimize burdens and maximize opportunity.