This one simple regulation will solve every teen's problems online

The Senate hauled in Facebook to explains its research on teens. At some point, we will need to admit that our problems are partly caused by technologies amplifying our own flaws.

First up, Facebook faces the fire. Then later, some news and laws and filings I’ve been following.

Over the past two weeks, the Senate has held two hearings spurred by reports from the Wall Street Journal that Facebook knew Instagram can worsen body-image issues for teen girls. Last Thursday, the Senate hauled Facebook’s Antigone Davis in front of committee to explain the first WSJ report. This week, Frances Haugen, the whistleblower who has been working with the WSJ to publish The Facebook Files series, took the stand.

According to the WSJ, the most damning things that Facebook found were that,

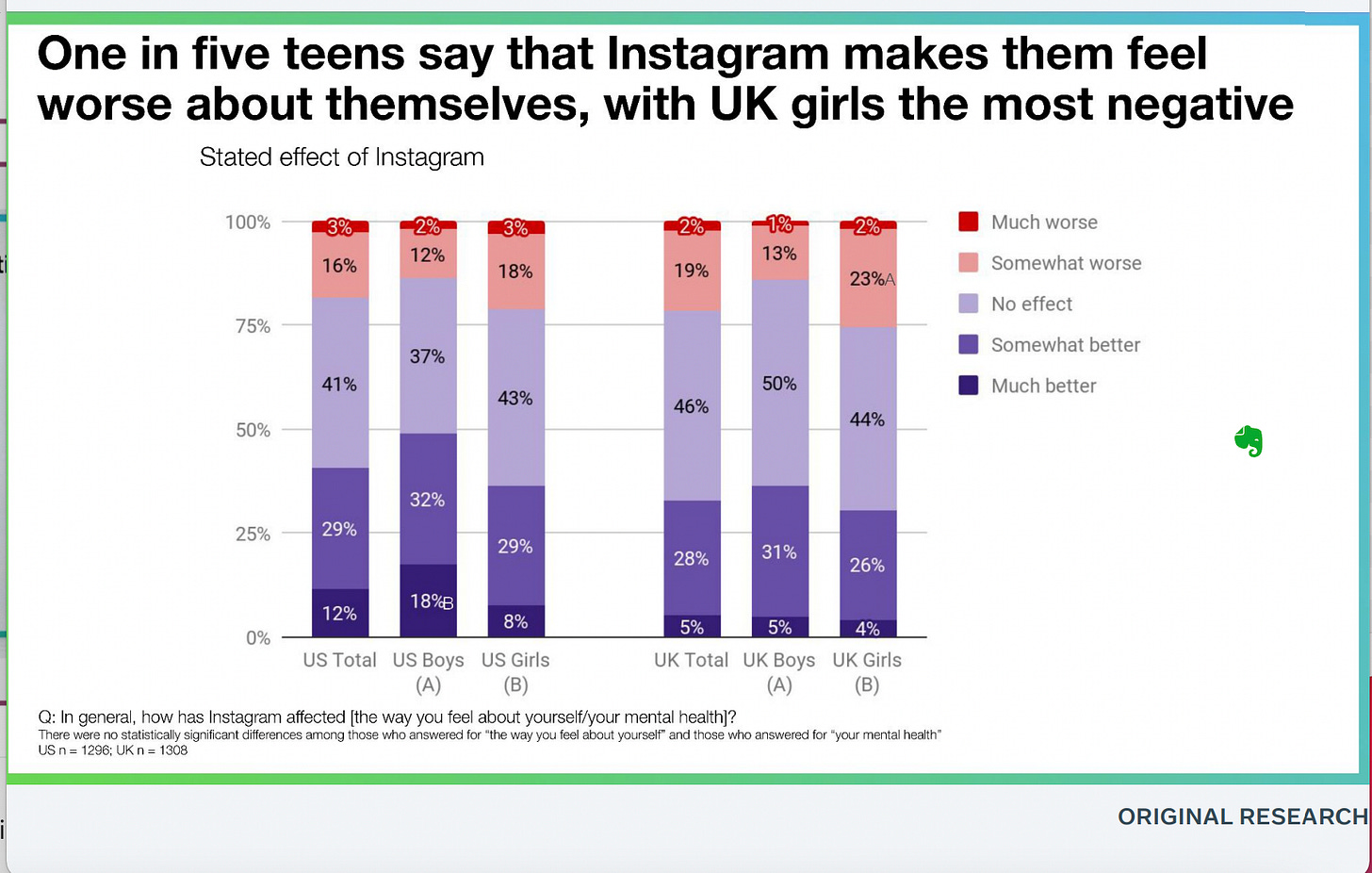

“Thirty-two percent of teen girls said that when they felt bad about their bodies, Instagram made them feel worse”

“We make body image issues worse for one in three teen girls,” said one slide from 2019, summarizing research about teen girls who experience the issues.

“Among teens who reported suicidal thoughts, 13% of British users and 6% of American users traced the desire to kill themselves to Instagram, one presentation showed.”

In response, Facebook published a blog with refutations and context, including two slidedecks (1,2) from two studies where the WSJ had pulled screenshots. Facebook is notoriously secretive of these reports, so they are worth reading in full, separate from my analysis.

The takeaway: Having read all the material, it doesn’t look as bad for Facebook as the WSJ reporting originally suggested. Still, the research shows that there are serious concerns, especially with body image and social comparison that need careful attention.

So what was released? Apparently, in 2019, Facebook researched hard life moments, 22 different topic areas where people struggle including body image, loneliness, social comparison, family stress, and suicidal ideation. Two separate studies were conducted. The first study was a survey of 22,410 users across the US, Japan Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, and India aged 13 to 65+. The second study included a 40 person study group with participants aged 13 to 17, and an online survey of 2,503 teen-aged Instagram users in the UK and the US.

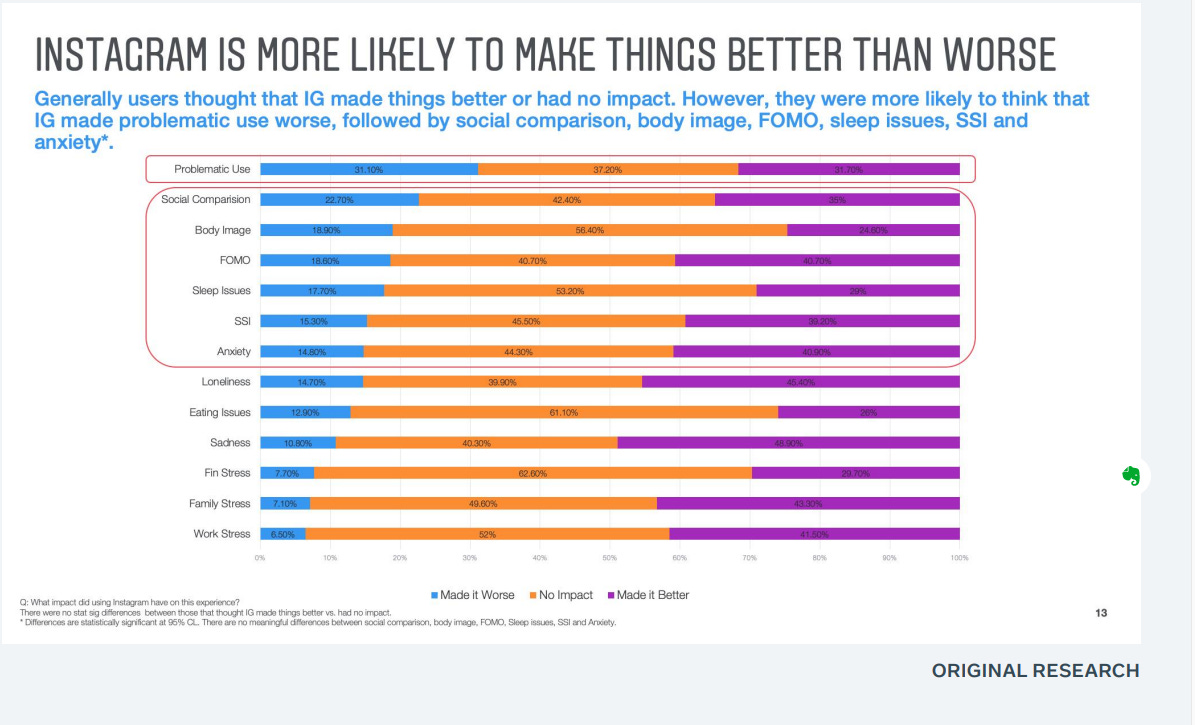

The chart below, like the rest of those in the post, is clipped from Facebook’s slides. What it shows is that Instagram is more likely to make things better than worse across a range of hard life issues when all age groups are included. I was most surprised to learn that most users don’t think Instagram makes this worse or better. There is, it seems, a lot of people who aren’t really concerned about the tech. Problematic use of tech was the only area where the two sides were about even.

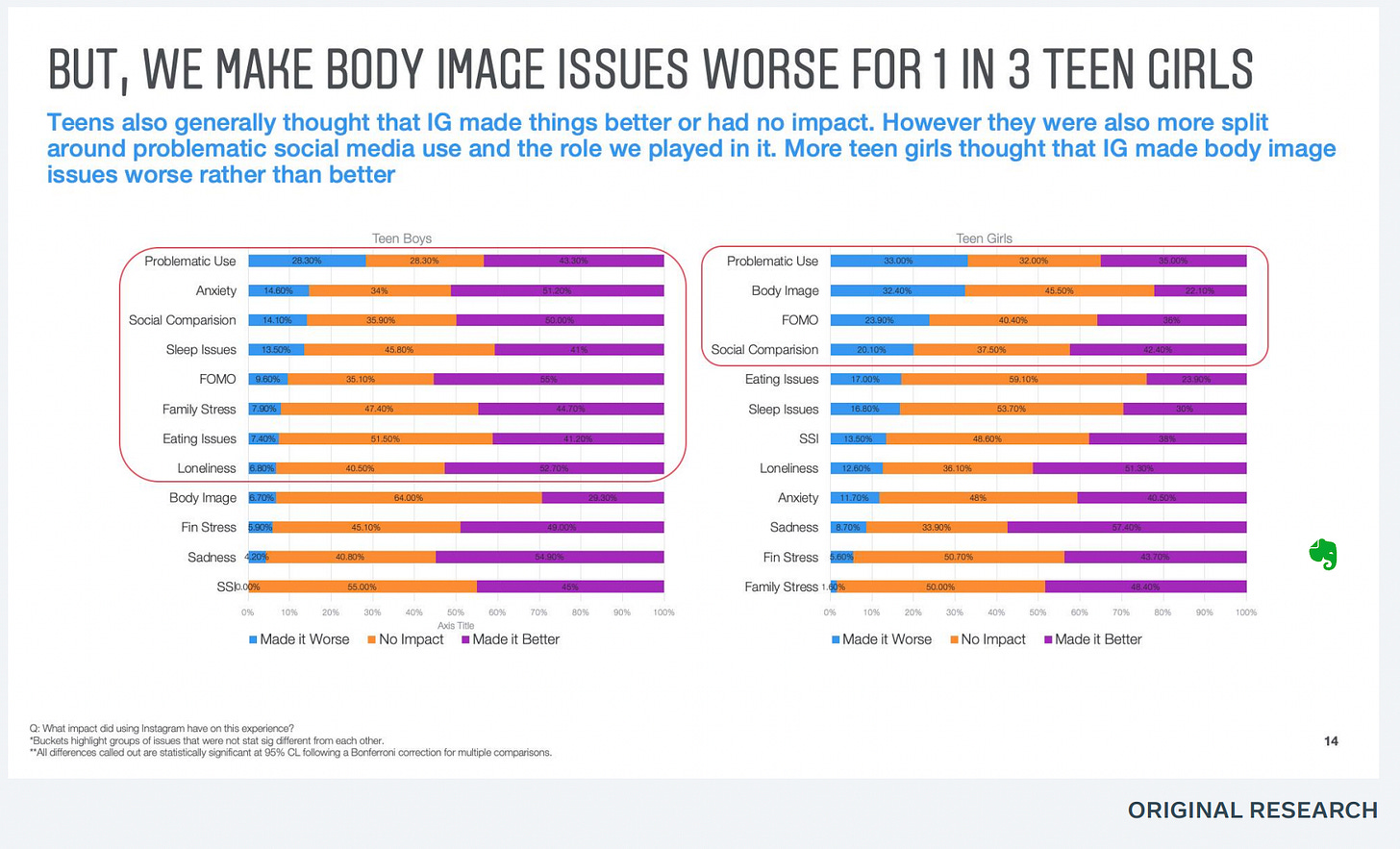

When just teens were asked, yet again, a higher number believed that Instagram made things better than worse in nearly every hard life issue, except for one. More teen girls said that body image issues were made worse by Instagram.

The second study may have interviewed fewer people, but it came to similar conclusions. Yes, the WSJ was right that one in five teens says that Instagram makes them feel worse about themselves. But of the four left, two of those would have said that it has no effect while the other two would have said it makes them feel better.

Not surprisingly, this second report also found that teens not satisfied with their lives are more likely to say Instagram makes them feel worse, and those teens that struggle with mental health say that the platform makes it worse. For their own part, Facebook rolled out a series of changes after this research was pulled together to give teens resources to deal with mental health problems.

Now on to the infuriating part. Both hearings infantilized teens. Yes, it is cringeworthy that Senator Blumenthal doesn’t understand finsta accounts, but it is even more worrying that leaders believe teens and adolescents aren’t thinking.

Teens are thinking about the impact of tech, the surveys show. They blame Instagram for increases in anxiety and depression. They want to spend less time on the app, but “feel like they have to be present.” They also expressed that they “feel ‘addicted’ and know that what they’re seeing is bad for their mental health but feel unable to stop themselves.” The surveys clearly highlight that teens want tools to understand and deal with their new world.

If the Senate really cared about making a difference, tech empowerment would have been a bigger part of the hearings. They could have invited Nir Eyal and Jonathan Haidt, who have very different views of social media, to discuss their commonsense rules for parents to follow. They could have talked about technical solutions like Rescue Time or Newsfeed Eradicator or Screen Time. They even could have talked about a bipartisan commission to study these impacts, as they did countless times in the late 1990s and early 2000s over violence on TV and video games.

Instead, Facebook and Instagram acted as the scapegoats for teen mental health issues. It’s fitting, the blame. It is the kind of tendency we should expect from the social media era. It’s clickbait governance for a clickbait world. It’s the one simple trick to regulation.

Connecting the dots isn’t hard. It is clear that Facebook does have an impact on mental health. A recent paper from Luca Braghieri, Ro’ee Levy, and Alexey Makarin is especially convincing. Using “the staggered introduction of Facebook across U.S. colleges” the authors were able to cleanly analyze the effects of the tech, finding that the “roll-out of Facebook at a college increased symptoms of poor mental health, especially depression.” Going one step further, they found additional evidence suggesting the results are due to Facebook fostering unfavorable social comparisons.

Their finding mirrors what Facebook’s own research found. In the United States, a society long dominated by competition, users felt that competition and social pressure were exacerbated by Instagram. But this was different than the experience in the UK. Bullying and social comparison were of the most concern over there, which tracks since the UK is famous for having a culture of bullying.

At some point, we will admit that these problems are caused by technologies amplifying our own flawed nature. At some point, we will admit that status games and expressions of power are played out in Instagram, as they are in offices, on the streets, and in homes. Instagram didn’t invent body issues, our broken culture and our worst tendencies did that.

There’s an entire body of research developing to understand how social media affects us. It’s bigger than just teens. People use social connections on social media to think. People congregate online for a reason. They want to commune. They want to communicate with others. At core then, these technologies offer value. But they come with changes in politics and advertising and education and on.

To make sense of it all, I just released a complete overhaul of my working bibliography on social media. It starts at the most important part, with some commonsense rules and a list of the tech I use to stay focused. Send me research I am missing and tools you use because I want it to be useful to parents and researchers alike. I am already planning another update.

Finally, I’ll have more to say about Frances Haugen’s testimony next week, but there was one point that really stuck with me. I can’t remember when exactly, but Haugen admitted that the company faced tough decisions, and from her perspective, oftentimes decisions had to be made even though there weren’t great solutions to choose from. Choice under constraint.

danah boyd articulated something similar in responding to Zuboff’s "Surveillance Capitalism.” As boyd astutely pointed out, it is reasonable to read a lot of tech history backwards. A lot of problems occur because of inherent constraints, including a limited horizon. The decisions are locally rational, but end up being detrimental on a broader scale.

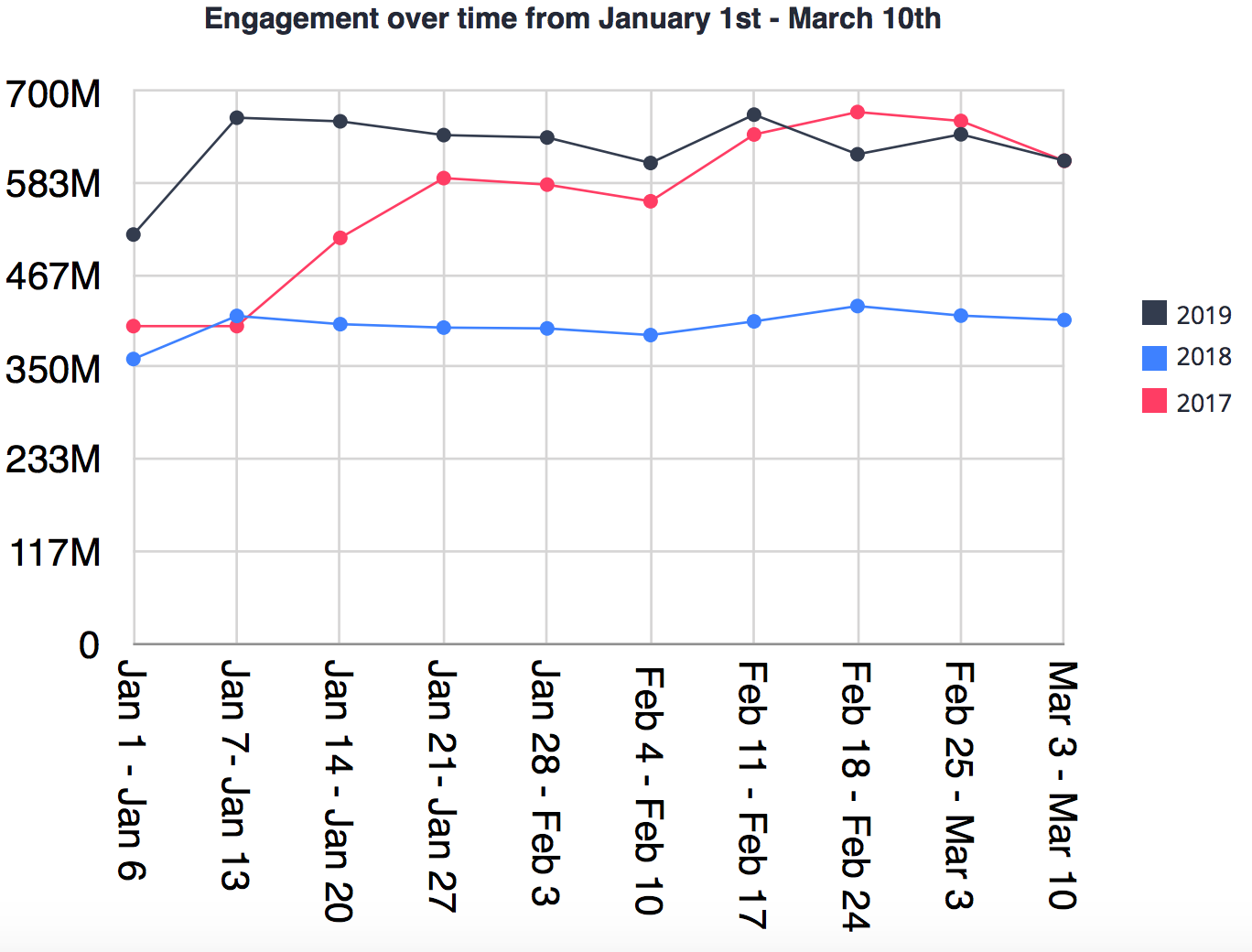

Haugen thought this kind of dynamic happened when Facebook implemented the meaningful social interactions change in 2018. It was this algorithm change that brought about divisiveness, Haugen stressed. Still, data from Neiman Lab a year after the change is hardly conclusive. Engagement increases in the beginning of 2019, not in 2018 after the policy change, as one would expect.

There are still so many gaps. Ignorance rules everything around me.

Odds and ends I’ve been tracking:

The Ohio Personal Privacy Act is the least bad bill I’ve seen. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

It seems like it shouldn’t have to be said, but TechFreedom is right. Let’s not apply NEPA to space.

Not a good trend, I’d say: “Roughly half of U.S. adults (48%) now say the government should take steps to restrict false information online, even if it means losing some freedom to access and publish content. That is up from 39% in 2018.” [Pew]

“I cannot, for the life of me, get over how much moving to online participation has changed the demographics and representation of who shows up to Council. It's like we're hearing from the other 90% of the city now.” Bella Chu, a councilmember for Redwood City, CA.

Privacy laws impose costs: “A single data subject access request (DSAR) and deletion request can cost a company $1,400. This is due to the aggregated total time of the support person, the legal person, and the R&D engineer who needs to go into the database and manually delete information off the servers.”

I was cleaning out some links and found this Nature article: “Scientists excavated ancient artefacts at Middle Stone Age sites dating back around 300,000 years at the Olorgesailie Basin, in southern Kenya. They uncovered weapons made of materials that could not be found there, suggesting hominins at the time may have exchanged goods with others.” Modern humans emerged around 200,000 years ago, so we have been trading as long as we have been a species.