The abundance agenda

Context to my recent Boston Review piece, the Henry Adams curve, and a list of action items to make the abundance agenda happen

There are two stubborn truths about our modern economic world.

First, we are fabulously wealthy.

Compared to the 1800s, the average person on the planet has been enriched in real terms by some 1550%. In the U.S., that number is even more dramatic. Currently, we are 2100% more wealthy than we were in 1800.

Today we have cars and air conditioning and therapeutic drugs and electric stoves and iPhones and skyscrapers and so much else. The Great Enrichment, Deirdre McCloskey calls it.

But there is a second, more recent truth, that beguiles us. Growth rates in the U.S. seem to be stalling out.

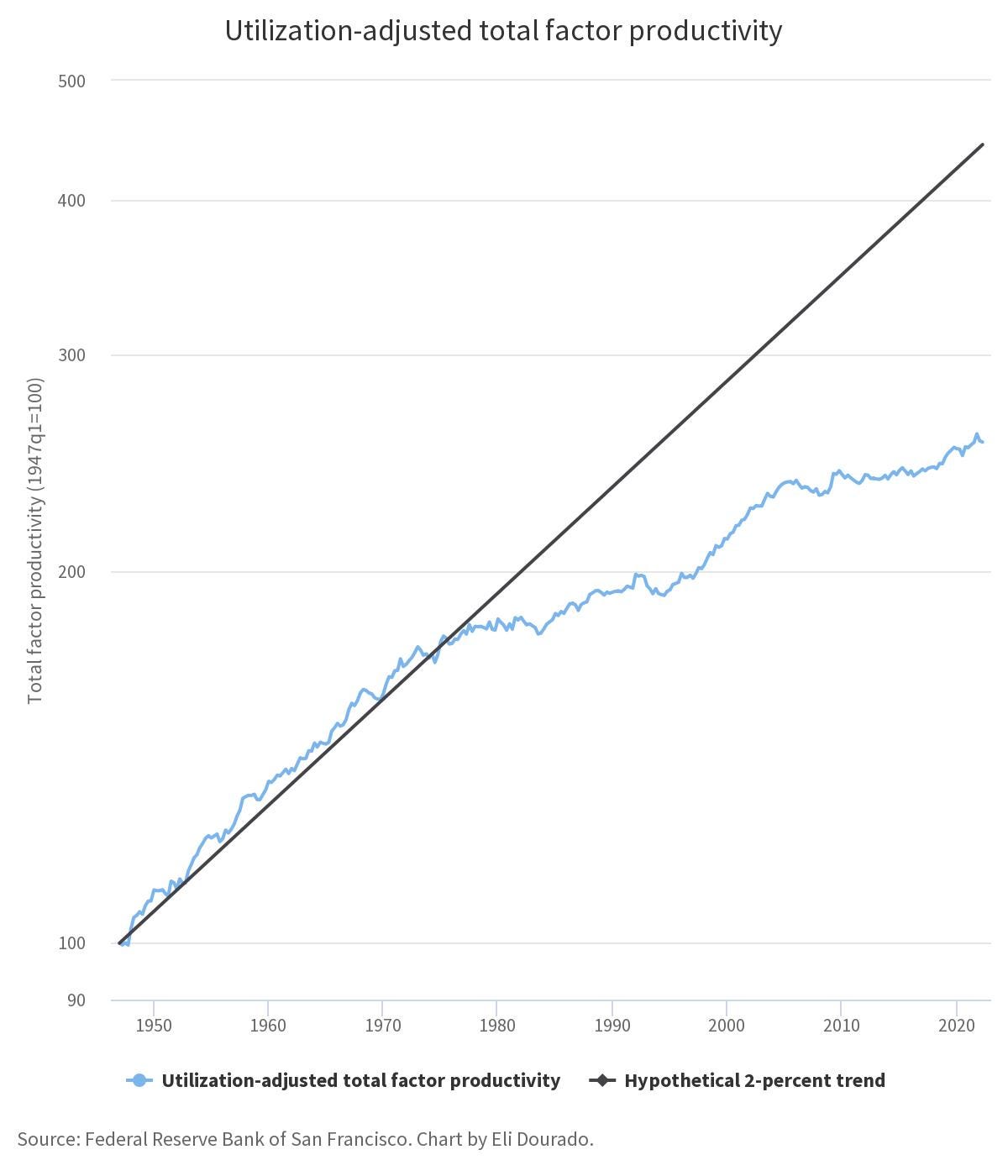

Sometime in the early 1970s, we got off track. After the war but before the 1970s, the prime mover of the economy, the productivity growth rate, was chugging along at about 2% per year. But then it slowed down to around 1% per year starting in the 1970s.

There is a lot of documentation supporting the slowdown. Eli Dourado even has this handy site to show you the yearly trends:

Had we grown 2 percent per year, the median household would be twice as wealthy as it is today. The median household would have around $150,000 in income instead of today’s $79,900. Using a more sophisticated model, James Pethokoukis was able to work out that there’s a hole amounting to $11 trillion.

So what happened in the 1970s? There’s a really strong case that the rise in energy prices is a big culprit.

A couple of years ago, Nobel Prize winner William Nordhaus pulled together all of the industrial data available going back to 1948 and then decomposed the changes in productivity growth. The results were stark. “The slowdown was primarily centered in those sectors that were most energy-intensive, were hardest hit by the energy shocks of the 1970s, and therefore had large output declines.”

While the exact relationship between energy and productivity is complicated, there is an “extreme interconnectedness of energy and economic systems,” as one researcher framed it.

The full-length version of this argument can be found in J Storrs Hall’s “Where is My Flying Car?”, easily the most thought-provoking book I have read in the past two or three years. The book, on the face of it, is about flying cars. But it is fundamentally about the flying car as a metaphor for an economy-wide slowdown.

In a blog post that added some context to the book, Hall explained,

We have had a very long-term trend in history going back at least to the Newcomen and Savery engines of 300 years ago, a steady trend of about 7% per year growth in usable energy available to our civilization. Let us call it the “Henry Adams Curve.” The optimism and constant improvement of life in the 19th and first half of the 20th centuries can quite readily be seen as predicated on it. To a first approximation, it can be factored into a 3% population growth rate, a 2% energy efficiency growth rate, and a 2% growth in actual energy consumed per capita.

Here is the Henry Adams Curve, the centuries-long historical trend, as the smooth red line. Since the scale is power per capita, this is only the 2% component. The blue curve is actual energy use in the US, which up to the 70s matched the trend quite well. But then energy consumption flatlined.

The Henry Adams curve is Martin Heidegger's famous standing reserve operationalized. It is at the root of McLuhan's extensions of man. It is a measure of power that we all have access to.

My recent piece in the Boston Review is about reversing these trends. It argues for a political agenda based on energy abundance and abundance more broadly:

Abundance is a big tent because a lot of changes are needed. We need abundance in housing, infrastructure, medicine, education, and well-paying jobs. Achieving the abundance agenda will mean the development of clean geothermal energy and next-generation nuclear. Dense housing needs to be built, the electrical grid needs upgrading, airports need investment, and a huge range of environmental projects need to be pursued. There is a lot of work to be done to give all people the resources for a good life.

So what does the abundance agenda look like in practice? Eli has laid out some of the action items:

If we wanted to raise American productivity, for example, we could simplify geothermal permitting, deregulate advanced meltdown-proof nuclear reactors, make it easier to build transmission lines, figure out why high-speed rail is so expensive, fix permitting generally, abolish the Jones Act, automate our ports, allow drones to operate autonomously, legalize supersonic flight over land, reduce occupational-licensing requirements, train more medical workers, build more hospitals, revamp our pandemic-response institutions, simplify drug approvals, deregulate land use to allow denser housing and mixed-use neighborhoods, allow more immigration, cancel inefficient programs, restrict cost-plus procurement contracts in favor of more effective methods, end appropriations based on job creation, avoid political direction of scientific research, and instill urgency in grantmaking.

And there is more. We also need to focus federal dollars on anti-aging research to extend healthy years, expand wildlife corridors through public-private partnerships, direct monies to tackle atomically precise manufacturing, develop commercialism in space, speed up and modernize municipal permitting processes, refactor and simplify our regulatory regimes, better understand atmospheric aerosols to help climate restoration, create cheap UV lights to kill viruses, set up moonshots for carbon sequestration and for sea oxygenation, eliminate disease-bearing mosquitoes, allow better sunscreens on the market, make sure everyone can order prescription glasses online and access telehealth services, plant trees in targeted areas, develop cheap metagenomic scanning for biosecurity, and build desalination plants to help with water constraints, just to name a few.

All of these goals are within our reach. We just need to roll up our sleeves and get to work.