The 15 hour workweek is a dream in search of economic roots

exformation #6 | The FTC is changing, big tech isn't a monolith, iOS 14.5 shifts the ad ecosystem + much more

A tech policy newsletter from an outsider.

Free at the point of consumption.

Delivered every Monday (+/- a couple hours).

News, notes & quotes

Senator John Kennedy reintroduced the Don’t Push My Buttons Act. From the release: “The Don’t Push my Buttons Act would narrow the scope of the liability limitation provided under Section 230 of the Communications Act, denying immunity to platforms that use algorithms to optimize engagement by pushing divisive content into users’ feeds.” The text is here.

Kennedy again: “Many social media platforms collect data to identify their users’ ‘hot buttons’—divisive issues that create strong emotional responses or reactions. The companies then employ algorithms that intentionally show their users content designed to agitate them.”

Kennedy’s bill reminds me of some work from our econ lab, which I detailed in this Twitter thread:

Big changes are underfoot at the FTC. Chair Lina Khan announced an open meeting for this week, the second in less than a month. The Policy Statement on Prior Approval and Prior Notice Provisions in Merger Cases will likely be rescinded while a proposed Policy Statement on Repair Restrictions Imposed by Manufacturers and Sellers will likely be adopted. Draft language on the proposed policy has yet to be released.

Both Facebook and Amazon have sought the recusal of Chair Khan from their pending FTC cases.

Also in the FTC space, Tyler Cowen also alerted me to this: “While some staff turnover in the wake of an administration change is routine, law firm leaders said the number of agency lawyers seeking out career options outside the FTC appears to be high now and they are anticipating more later in the year. They attribute that, at least in part, to agency lawyers who have different views compared with [Chair] Khan’s ideas of what constitutes antitrust behavior and how to bring cases. In particular, private practice antitrust lawyers told the National Law Journal that some senior career lawyers at the FTC, including people who did not vote for President Donald Trump, might not align with Khan’s vision of antitrust enforcement or they are uncomfortable with the work they may be asked to do.” Is the deep state anything more than the bureaucratic state? [Law.com]

Yet another week has passed and still, the White House has yet to nominate a lead for DOJ’s antitrust division. In April, Jonathan Kanter and Jonathan Sallet were rumored as the top picks.

On the Cuba front:

Big tech isn’t a monolith as Emily Birnbaum reports in Politico: “The declining prominence of IA, a nine-year-old group that used to call itself ‘the unified voice of the internet economy,’ comes as a larger fragmentation is splitting the tech industry’s lobbying efforts into factions, according to more than a dozen current and former employees, congressional aides and tech company employees who spoke to POLITICO on condition of anonymity. But they said the association’s internal dysfunction has also diminished its impact in Congress and in public debates about Silicon Valley’s expanding array of lawsuits, legislation and regulatory threats.”

The biggest threat to Facebook probably isn’t antitrust scrutiny, but the changing ad ecosystem, especially those brought on by iOS 14.5. From Bloomberg: “Facebook advertisers, in particular, have noticed an impact in the last month. Media buyers who run Facebook ad campaigns on behalf of clients said Facebook is no longer able to reliably see how many sales its clients are making, so it’s harder to figure out which Facebook ads are working. Losing this data also impacts Facebook’s ability to show a business’s products to potential new customers. It also makes it more difficult to ‘re-target’ people with ads that show users items they have looked at online, but may not have purchased.”

From the WSJ: “Tinuiti’s Facebook clients went from year-over-year spend growth of 46% for Android users in May to 64% in June. The clients’ iOS spending saw a corresponding slowdown, from 42% growth in May to 25% in June. Android ad prices are now about 30% higher than ad prices for iOS users, Mr. Taylor said. Tinuiti clients’ overall spending on Facebook increased—Android users gained a greater share of it, Mr. Taylor said.”

The EU is delaying a proposed digital tax. The NYT: “The United States secured a diplomatic victory in Europe on Monday when European Union officials agreed to postpone their proposal for a digital levy that threatened to derail a global effort to crack down on tax havens.”

Also out of Europes: “European consumer groups filed a complaint against WhatsApp over a controversial privacy policy update on Monday, alleging the platform’s ‘intrusive’ notifications pushing the update breached European Union commercial practices.” [The Hill]

A project to follow, New Science, just launched, and it is being run by Alexey Guzey, Mark Lutter, and Adam Marblestone: “Our goal is not to replace universities, but to develop complementary institutions and to provide the much needed ‘competitive pressure’ on the existing ones and to prevent their further ossification. New Science will do to science what Silicon Valley did to entrepreneurship.”

China has been cracking down on its own tech companies. South China Morning Post has this report on the big changes. Part of this includes tightened restrictions on the overseas listings of homegrown companies.

The new European-American ocean-monitoring satellite Sentinel 6 has started delivering ultra-precise measurements of rising sea levels on Earth a six-month shakedown period.

NASA is leading an effort, working with the Department of Energy (DOE), to advance space nuclear technologies. The government team has selected three reactor design concept proposals for a nuclear thermal propulsion system. The reactor is a critical component of a nuclear thermal engine, which would utilize high-assay low-enriched uranium fuel. [NASA]

Facebook’s Zuckerberg: “We want to build the best platforms for millions of creators to make a living, so we're creating new programs to invest over $1 billion to reward creators for great content they create on Facebook and Instagram through 2022. Investing in creators isn't new for us, but I'm excited to expand this work over time. More details soon.”

Ransomwhere is an open, crowdsourced ransomware payment tracker. You can browse and download ransomware payment data or help build their dataset by reporting ransomware demands.

Retro Game Mechanics Explained is a YouTube series of in-depth explanations of old video games. Highly recommended.

Jason Crawford explains why he embraces the term solutionist in MIT’s Technology Review: “To embrace both the reality of problems and the possibility of overcoming them, we should be fundamentally neither optimists nor pessimists, but solutionists… Solutionists may seem like optimists because solutionism is fundamentally positive. It advocates vigorously advancing against problems, neither retreating nor surrendering. But it is as far from a Panglossian, ‘all is for the best’ optimism as it is from a fatalistic, doomsday pessimism. It is a third way that avoids both complacency and defeatism, and we should wear the term with pride.”

Papers and research

"Digital Addiction" is a new paper that I'm still chewing on: “Many have argued that digital technologies such as smartphones and social media are addictive. We develop an economic model of digital addiction and estimate it using a randomized experiment. Temporary incentives to reduce social media use have persistent effects, suggesting social media are habit forming. Allowing people to set limits on their future screen time substantially reduces use, suggesting self-control problems. Additional evidence suggests people are inattentive to habit formation and partially unaware of self-control problems. Looking at these facts through the lens of our model suggests that self-control problems cause 31 percent of social media use.”

Ancient weights helped create Europe’s first free-market more than 3000 years ago: “Through informal networks, Mesopotamian merchants established a standardized system of weights that later spread across Europe, enabling trade across the continent. The advance effectively formed the first known common Eurasian market more than 3000 years ago.”

Mozilla Foundation published “YouTube Regrets,” which is a crowdsourced investigation into YouTube's recommendation algorithm.

Wikihole: “New Mathematics or New Math was a dramatic change in the way mathematics was taught in American grade schools, and to a lesser extent in European countries and elsewhere, during the 1950s–1970s. Curriculum topics and teaching practices were changed in the U.S. shortly after the Sputnik crisis. The goal was to boost students' science education and mathematical skill to meet the technological threat of Soviet engineers, reputedly highly skilled mathematicians.”

The 15-hour workweek: a dream in search of economic roots

About a week ago, I finished listening to an episode of The Ezra Klein Show with James Suzman as a guest, talking about his new book, Work: A Deep History, from the Stone Age to the Age of Robots, and the idea of the 15-hour workweek.

Klein's opening monologue got me hooked. He began with one of the most famous essays in economics, a paper you debate ad nauseam in macro, John Maynard Keynes' "Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren."

Back in 1930, the father of Keynesianism predicted that we would be working for 15 hours each week. And we would do this while still being much richer than before.

Klein:

And the reason this essay still gets talked about and debated and written about today is that Keynes was interestingly right and wrong. The part of this that seems hard and probably seemed very out there when he did it, the calculations for how much richer we’d get in 100 years, that was not just right. If anything, it was conservative. We passed his predictions for income growth decades ago. And then we got even richer than that.

But you may notice we don’t work 15 hours a week. In fact, in an inversion of past history, the more money you make now, the more hours you generally work. It used to be the point of being rich was to not work. And now we’ve built a social value system. So the reward for making a lot of money at work is, you get to do even more work. And so people all up and down the income scale with levels of plenty that would have been shocking to anyone in Keynes’s time are harried, burnt out, always wanting more, feeling there’s not enough.

For a couple of years now, I've been wanting to revisit this paper and I was hoping that Klein and Suzman would tackle Keynes' paper on its own terms. This never happened, but it should have been done because it would have added a much-needed depth to the conversation.

Instead, Suzman sought to reverse Keynes. The "very advances in technology and income and productivity that Keynes predicted are actually the problem," keeping us from a 15-hour workweek. Speaking about the Ju/’hoansi tribe, Suzman points out that they "were deeply impoverished by modern standards. And yet they consider themselves affluent and enjoyed a degree of affluence as a result of that." In contrast, our modern world is "trapped in this cycle of ever pursuing more and greater growth, greater wealth, greater anything, it seems."

We're caught in modernity's treadmill. Yes, I thought. A hedonic treadmill.

Throughout much of the opening dialogue, I had hope, that is, until Suzman made a fairly large error saying, "And we’re working pretty much as long hours as people did in the 1930s when Keynes wrote the essay in the first place. So that’s another critical thing he got wrong."

Eh.

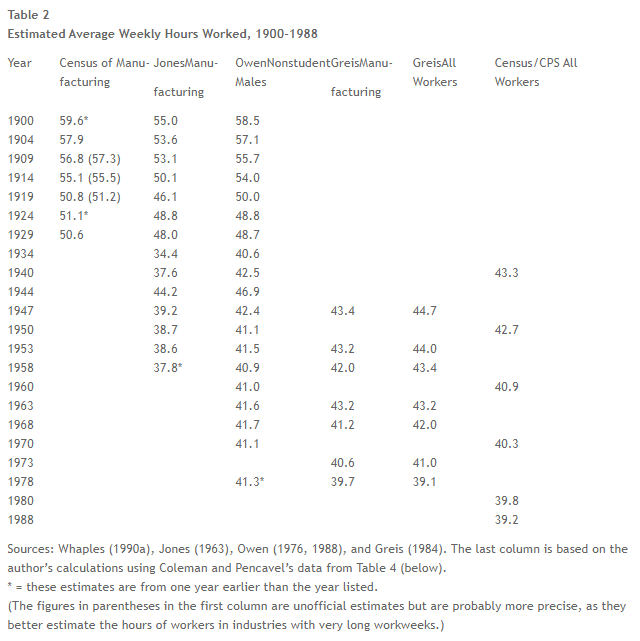

The table below charts a high and low estimate of average hours worked using data provided by the Economic History Association. Admittedly, data from the early 20th century does pose problems, but the trend is clear. Keynes wrote the essay in 1928 and U.S. estimates from next year suggested that workers were putting in 48 to 51 hours weekly. In 1988 that had dropped to around 39 hours per week. Currently, the BLS estimates that the average weekly hours worked is 34.7.

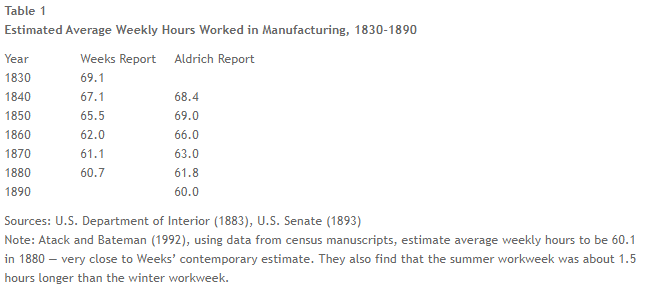

Back out the data into the 1800s and the trend comes into sharp focus.

Again, data from the 1800s has its issues, which are detailed here, but the economics profession has generally agreed upon this sharp decline.

Later in the discussion, Suzman explained that all of the basic needs of the Ju/’hoansi were met "pretty much on the basis of around 15 hours for women and 17 hours work week for men in terms of the food quest." He continued, "And then on top of that, they’d work a similar number of hours on domestic household activities, tasks like preparing food, making fires, fixing tools, and so on and so forth. In other words, that they worked much less than we did."

Roughly then, the Ju/’hoansi worked between 30 and 34 hours per work to get food and maintain household upkeep. Hunter-gatherers aren't working 15 hours weeks, they are working more like 30 hours each week.

The Keynes paper remains a fascination for economists because it's short at only 7 pages. More important, it is mysterious. There is no model, no data, no tables, nothing to support the claims that he makes. There is only a grand statement about a future of 15-hour workweeks.

Even with the data of the time, it is hard to reconstruct the lines of thought, as Ohanian (2008) explains,

Keynes does not provide any details on how he arrived at this forecast, and this raises the question of what economic theory or quantitative procedures he used to arrive at this number. The decline is much larger than a forecast produced from simply extrapolating the historical decline in hours worked. In particular, hours worked per capita declined about 10 percent in the United States between 1889 and 1929, and this same rate of decline between 1929 and 2029 generates a further 23 percent decline, far short of the two-thirds decline predicted by Keynes.

So how do economists understand this paper?

The standard model in economics emphasizes two different forces that enact upon the choice between income or leisure. The first, the income effect, happens when higher wages allow for more consumption of leisure. This is what Keynes was harping on. But the second force pulls in the opposite direction. The substitution effect occurs when work becomes more worthwhile and thus people work more. To be very specific, the slope of the indifference curve measures the marginal rate of substitution between leisure and income.

Understanding the push and pull between these forces, especially as they occur over two time periods, one of work and one of leisure, can take us far in explaining a variety of work patterns.

The typical response to Keynes was that he didn't see the ramp-up in retirement benefits and the extension of life years. People work in their relative youth and then retire to consume their leisure. So if you add in retirement to the equation, people seem to be working about a 15-hour workweek, according to economist Nicholas Crafts.

Seen in this light, the anti-work contingent makes much better sense, especially as a trend cordoned off among Millennials and Zoomers. If you have been told your entire life that you aren't going to have retirement and won’t be able to afford a home to eventually haunt, it makes sense why you'd push for fewer hours today. Consuming later ain't happening, so might as well consume leisure now.

The income effect seems to dominates as a long-term trend. As the data tables above showed, US weekly work hours dropped from 60 hours in the 1800s to 34 hours currently. Over time, the US has chosen more leisure. When the scope of comparison is across nations, rather than across time, it is also the case that people in richer nations work fewer hours.

Still, the substitution effect seems to dominate within an economy. It is true, as Klein points out that, "In fact, in an inversion of past history, the more money you make now, the more hours you generally work." As the paper above confirmed, "Within countries, hours worked per worker are also decreasing in the individual wage for most countries, though in the richest countries, hours worked are flat or increasing in the wage. One implication of our findings is that aggregate productivity and welfare differences across countries are larger than currently thought."

Jones and Klenow (2016) was another path not taken in the conversation. This paper incorporated consumption, leisure, mortality, and inequality into a summary statistic, allowing for a comparison among countries which shows that “Western Europe looks considerably closer to the United States, emerging Asia has not caught up as much, and many developing countries are further behind.” An extension of the model found “welfare for Black Americans was 45% of that for White Americans in 1984 and rose to 64% by 2019.”

On this most recent reread of Keynes, I’m left feeling that this speech was a dialogue written by a court jester. The speech isn’t about the eventualities of our future, as much as it's about the possibilities of a future. Keynes left us a ball to untangle. Klein and Suzman didn’t do much tugging at key threads, which would have made it a better dialogue.