Data Centers Make Easy Targets For Rising Energy Bills, But They Are Poor Scapegoats

Virginia found data centers "are currently paying full cost of service." Policymakers should focus on rate design and regulation, not restriction.

Last month, Senators Elizabeth Warren, Chris Van Hollen, and Richard Blumenthal sent an angry letter to the CEOs of leading tech companies, singling out data centers for climbing energy bills. They are big and energy-hungry, after all, and it seems that tech companies are “passing on the costs of building and operating their data centers to ordinary Americans as AI data centers’ energy usage has caused residential electricity bills to skyrocket in nearby communities.” The numbers sound terrifying:

As a result of the combined energy needs of AI data centers and cryptocurrency miners, electricity bills are estimated to rise 8% averaged nationwide by 2030 and up to 25% in states like Virginia with a high concentration of data centers.

Political pressure has only intensified since then. Just this week, President Trump called on tech companies to “pay their own way” and not burden local ratepayers with infrastructure costs. Microsoft quickly pledged not to seek property tax breaks or allow its facilities to drive up electricity rates. This high-level attention reflects genuine concern about surging electricity costs but it also risks cementing a misleading narrative.

While a 25 percent price hike sounds dire, when you look at actual estimates from Virginia, this increase represents the top-end estimate, with a middle range projection of a 7 percent increase. It’s not nothing, but it is not evidence of a price spiral from AI. The real kicker is that this same research found that data centers have paid their way, though this might not continue if policy doesn’t change.

Empirical analysis on this question is clear. Data centers haven’t been the big driver for rising energy prices. It’s been inflation. Counterintuitively, this research finds that “the greatest price increases typically exhibited shrinking customer loads.” Data centers use a lot of power, but whether that power consumption automatically translates into higher bills for everyone else depends on regional policy choices and how the individual contracts are structured.

Energy cost projections are notoriously difficult to get right, and advocates frequently exploit this uncertainty by embedding their preferred policy solutions within seemingly technical assumptions. To understand just what was being predicted, I followed the 25 percent increase stat in the letter to a New York Times article and then to a series of Carnegie Mellon University (CMU) reports. The numbers are detailed here:

Home to the nation’s largest data center concentration, the region is projected to require an additional 100 TWh of electricity by 2030. Our analysis shows that, under current policies, more than 25 GW of aging and costly coal plants would continue operating largely to meet the added electricity demands from data centers, plants that would otherwise be on track to retire. This added generation drives a projected cost increase of more than 25% in Central and Northern Virginia—the highest regional increase in the model. Under these conditions, price spikes similar to those seen in the December 2024 PJM capacity market auction may become more common.

Still, it doesn’t make much sense to me why the CMU report assumes that “increasing generation from older coal plants—while expensive to operate—is still less expensive in the short-run than building new gas.” Why would expensive coal generation be the marginal resource rather than new natural gas combined cycle plants? I asked Claude about these assumptions and it responded, “You’re right to be skeptical. This reads more like advocacy research designed to support predetermined policy conclusions than a neutral capacity expansion analysis.”

Virginia is home to about 13 percent of all global data centers, with numbers expected to grow substantially in the near term. To plan for this future growth, Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (VJLARC) commissioned a report from E3, a widely respected energy consulting firm, to figure out what data center growth would mean for the state. In December 2024, the report was released and it was accompanied by a review of electric infrastructure and rate impacts from projected data center growth.

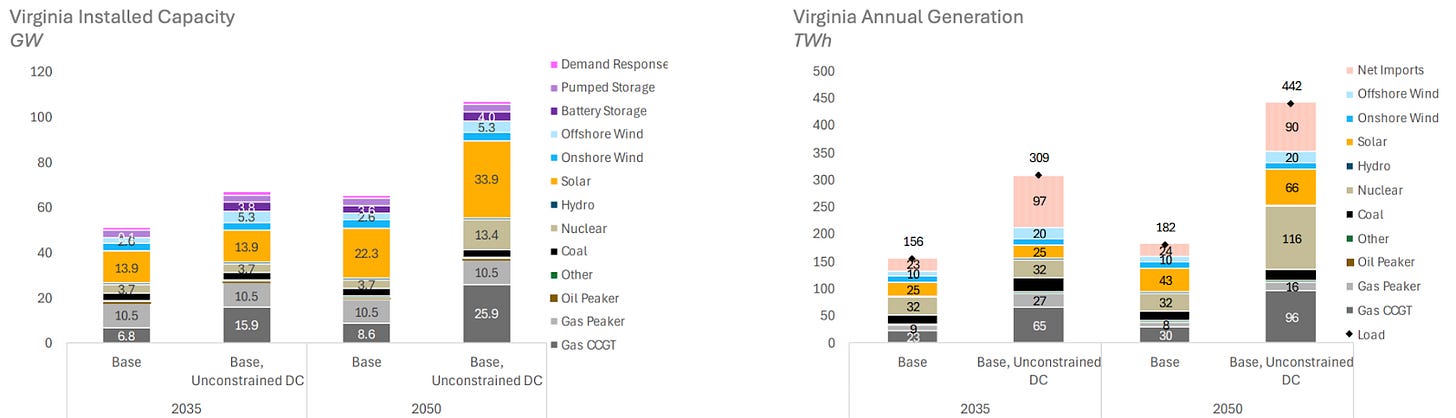

While these forecasts are never perfect, they estimated load growth demands assuming no new data centers, unconstrained data center growth, and a moderate projection. Then these load growth scenarios were varied assuming that the state’s utilities did or did not comply with the Virginia Clean Economy Act’s (VCEA) requirement of 100 percent zero carbon generation portfolios by 2050. Assuming that Virginia doesn’t meet VCEA standards, which the law allows for, and assuming unconstrained data center growth, “Virginia is projected to add significant amounts of new gas capacity at an accelerated rate in the near term, compared to the no growth case.” As the graph below illustrates, coal is nowhere near the level that the CMU report assumes. Though, to be fair, this may come from net energy imports from nearby regions.

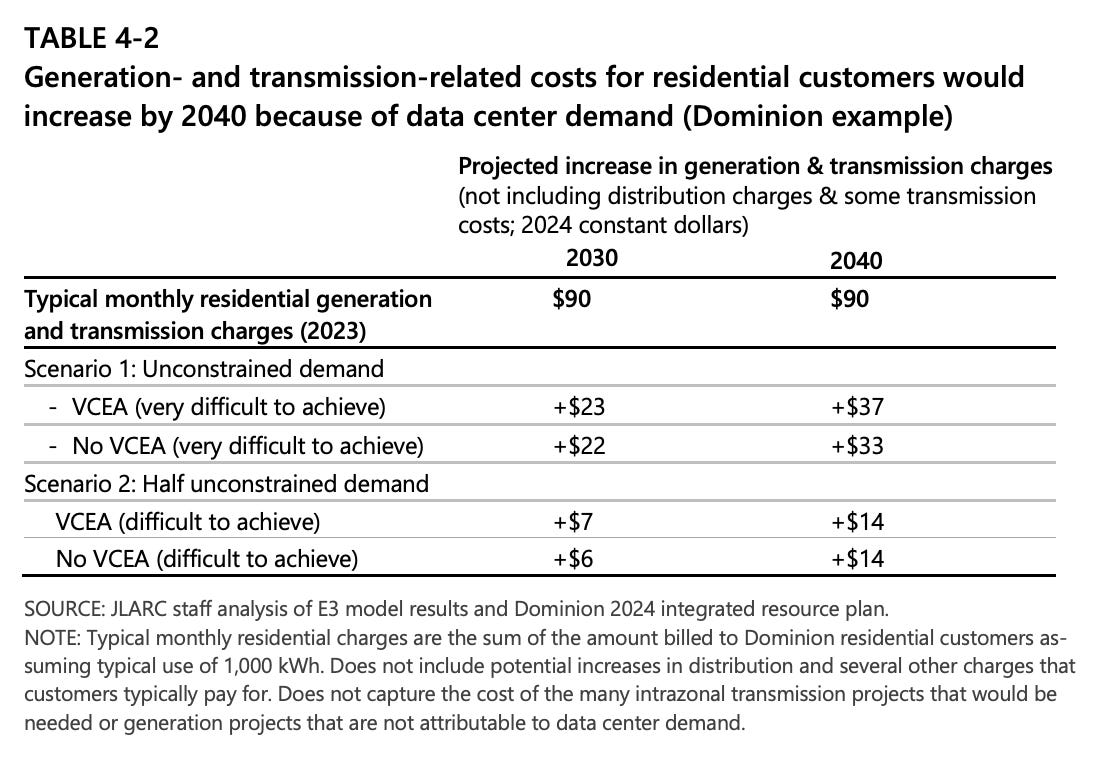

In spite of these differences, the VJLARC report estimated that 2030 energy prices could see a rise of 25 percent, similar to the CMU report. This was a top-end estimate from the unconstrained scenario, assuming that data centers could be “sited, built, and interconnected as fast as the market desires.” But, as the report continued, “in practice, constraints on the pace of infrastructure development may limit how quickly these facilities can add electric demand to the system.” Instead, if there were constraints in data center growth, prices would be a much more manageable 7 percent. Energy policy is hardly immune to politics. Advocates lead with the most alarming figure while burying the assumptions that drive the numbers. The headline number is technically defensible, but only under an extreme scenario.

But the real narrative violation is that in reviewing the past few years of price increases, the VJLARC report found that “current rates appropriately allocate costs to the classes and customers responsible for incurring them, including data center customers.” That finding directly undercuts the popular claim that data centers have been quietly shifting their costs onto ordinary ratepayers.

These results are corroborated by a new paper from researchers at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) looking at price increases from 2019 to 2024. They reached a conclusion that cuts against the current thinking about data centers: load growth is associated with lower retail prices. To be fair, the LBNL paper and the ratepayer review both look backward to understand what drove retail electricity prices, so these findings might not hold in the future.

This slide deck offers a great overview of all the work behind the LBNL paper, though there are six trends worth highlighting because they explain a lot of what has happened with price hikes:

National-average nominal retail prices have largely tracked economy-wide inflation in recent years, so real prices have been flat;

Residential customers have faced larger recent price increases than have commercial and industrial customers;

State-level retail electricity price trends vary, with some states’ prices rising much faster than inflation;

Natural disasters, extreme weather, and wildfire mitigation have significantly increased prices in some states;

Natural-gas price fluctuations have been among the largest factors impacting year-to-year variations in retail electricity prices; and

Many state-level renewable portfolio standards—which require that energy is sourced from renewable energy sources like wind, solar, and geothermal—have increased retail electricity prices.

I think most people would be surprised to learn that states with shrinking load tended to see higher prices. This helps to explain, partly, why California is having an explosion of energy prices. Rooftop solar mandates are driving down use, which means that fixed grid costs were spread over fewer kilowatt-hours. When new load arrives and can be served largely with existing infrastructure, it dilutes embedded fixed costs, pushing average prices down. It’s this chain of events, the LBNL paper details, that helps to explain why a 10 percent increase in statewide load is linked to a 0.6¢/kWh reduction in prices.

But what might we expect in the future as data centers continue to expand? Amazon commissioned E3 to study this, and their framework helps to clarify what might happen in a region in one of three different scenarios:

Small increases that the grid can handle — This describes most of the recent data center growth. When electricity demand rises, utilities can serve new customers using power plants and transmission lines that already exist. And if the incentives are right, everyone’s average price can fall because fixed costs get spread across more customers.

Growth that requires new infrastructure — Sometimes demand grows enough that utilities need to build new power plants or transmission lines. In this case, what happens to residential electric bills depends entirely on who pays for this new infrastructure. If the new customer, like a data center, pays the marginal infrastructure costs, the effect on other ratepayers is neutral. If the new customer also helps cover embedded fixed costs, average prices for residents decline. If those costs are instead socialized, prices for other customers rise. It depends entirely on the cost allocation equations.

Massive growth that transforms the whole system — Occasionally, electricity demand expands so much that it rivals the size of the existing grid itself. Meeting this demand requires utilities to build new infrastructure at an unprecedented scale. In these transformational load scenarios, the traditional approach to setting electric rates breaks down and avoiding unfair cost-shifting requires custom contracts that spell out exactly who bears which risks.

What I take away from the totality of this evidence is this: whether ordinary consumers bear the costs of data center growth is a policy choice. Data centers do not inherently raise residential electricity bills. They do so only under rate designs that allocate infrastructure and system costs in ways that allow residential customers to subsidize large, high-load users. In Georgia, for example, the state’s largest utility is set to double their total generation over the next five years while also cutting the average household electric bill by more than 50 percent. And rightly, the VJLARC report suggests “establishing a separate data center customer class, changing cost allocations, and adjusting utility rates more frequently could help insulate non-data center customers from statewide cost increases.” Read this way, the projected price increases might be better understood as a warning about cost allocation methods, which are opaque and highly technical as this 79-page presentation underscores.

Energy contracts also have a part to play. Many contracts include capacity reservation fees. Data centers pay for reserved power whether or not they use it, helping utilities plan infrastructure investments without passing emergency capacity costs to other ratepayers. Some agreements include interruptible service clauses. The data center gets discounted rates but must curtail usage during peak demand periods. Economic development agreements are also common where data centers will fund energy infrastructure upgrades. These arrangements can create win-win outcomes.

The senators who wrote to Amazon aren’t entirely wrong to be concerned. Virginia’s electricity demand is genuinely surging, and if that growth is managed poorly, residential customers could get stuck with the bill. And data centers make for a convenient target. They’re big, they’re owned by wealthy tech companies, and AI is everywhere in the news. But if we’re going to fix electricity pricing problems, we need to understand what’s actually causing them. Blaming data centers for rising electricity bills is easier than reforming how we allocate infrastructure costs, but only one of those approaches will actually help ratepayers.

Until next time,

🚀 Will